As the Emotet botnet kill switch is deployed this weekend, it is a good chance to reflect on how Emotet grew to be one of the world’s most infamous botnets and the lessons that security teams can learn to protect their organisations against similar threats.

What is Emotet?

A botnet is a network of hijacked computers and devices infected with malware and controlled remotely by cybercriminals. This network is then used to send spam and launch Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. It can also be rented out to other cybercriminals.

The Emotet botnet has been a thorn in the side of security teams for many years and has infected hundreds of thousands of devices since 2014. At its peak, Emotet’s infrastructure comprised of hundreds of servers around the world, allowing operators to spread to new machines, offer Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) and improve the resilience of the network.

How did Emotet grow?

Emotet was a cyber threat that posed a significant risk to organisations across the globe. It was first identified in 2014 and initially used as a banking Trojan. Emotet later evolved to deliver dangerous payloads and in 2020 it was classified as one of the most prevalent malware strains in the world. However, on 27th January 2021 Emotet was disrupted by a coordinated global operation by law enforcement and judicial authorities.

Prior to its takedown, the malware was available to organised cybercriminal groups (OCGs) as malware-as-a-service, enabling them to obtain initial access to victims’ environments and install third-party malware such as TrickBot, Ryuk and IcedID.

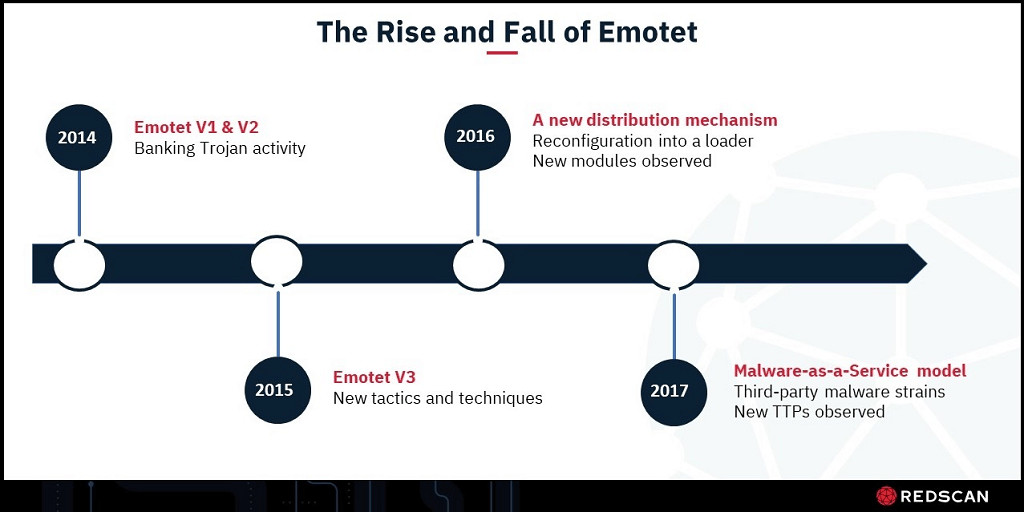

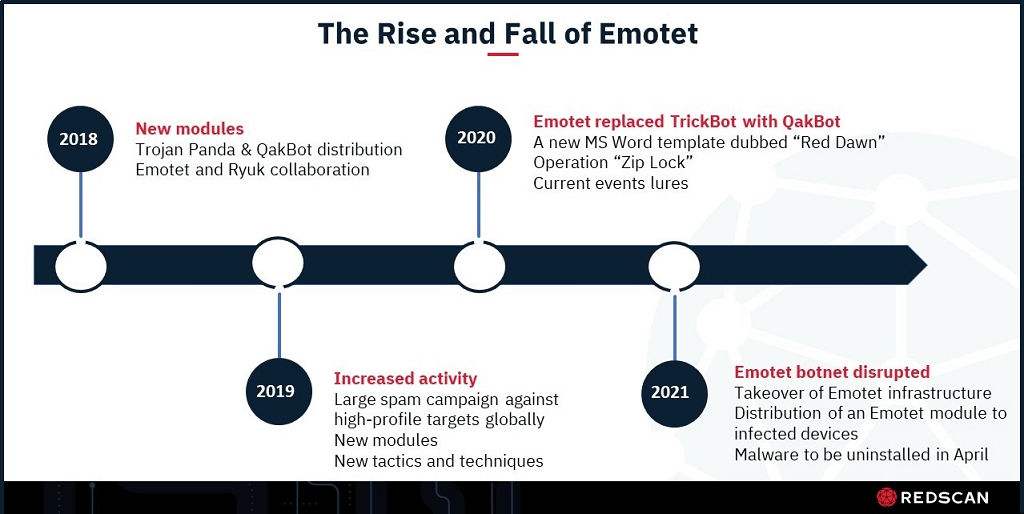

A timeline of the rise and fall of Emotet

In June 2014, security researchers detected the first ever recorded instance of the Emotet malware, which was being used as a banking Trojan to steal funds from accounts. A second version emerged in the autumn, when Emotet started using an Automatic Transfer System (ATS) for financial theft against a very limited number of Austrian and German banking clients.

In January 2015, Emotet returned to the stage with some new obfuscation features, including an integrated public RSA key and a partially cleaned ATS script, and was observed launching campaigns against a more diverse set of targets.

A major shift in 2016 saw Emotet’s evolution into a loader, allowing other OCGs to deploy second-stage payloads.

2017 marked a significant milestone in Emotet’s development. It was the first time it was observed to drop third-party malware strains such as the IcedID banking Trojan, as well as TrickBot, QakBot, Dridex and UmbreCrypt ransomware, as Emotet’s operators adopted a new MaaS model.

Just one year later, in 2018, Emotet began distributing Trojan Panda and this year marked the beginning of the Emotet and Ryuk gang collaboration.

2019 saw Emotet adopt new targets and new tricks. A large-scale malspam campaign targeted German, British, Polish and Italian organisations, and Emotet was observed using password-protected ZIP files with JScripts/Microsoft Word docs. Overall activity doubled compared to that in the previous year, exceeding 1 million spam emails per day.

After a pause, Emotet returned to the scene in July 2020 with a massive malspam campaign. In a major operational shift, it replaced the distribution of the TrickBot Trojan with QakBot (or QBot), a worm-like strain of information-stealing malware.

On January 27th 2021, EUROPOL announced that the infrastructure of the Emotet botnet had been disrupted and gang members had been arrested by the coordinated actions of law enforcement agencies across Europe and North America.

Why was Emotet so successful?

Emotet infections rose because of the malware’s good Command and Control (C2) infrastructure, frequent code updates, ability to evade detection mechanisms, and its modular nature.

As Emotet was malspam-based, it was typically delivered via email, which in most cases invited victims to open an attached document or visit a link to download one. The document delivery mechanisms changed regularly to hinder detection, but generally they had the same goal – to achieve initial access or to steal credentials from a victim.

Within those files attached to phishing emails, Emotet macros were almost always heavily obfuscated. Emotet operators usually hid information in document data and metadata to conceal encoded text, which was then decoded by the macro, and proved highly successful in infecting target networks. The huge amount of Emotet infections prove that many victims fell for the lures.

Watch this webinar to hear more about the legacy of Emotet

What will happen to Emotet on the 25th April?

On Sunday 25th April 2021, Emotet will disappear without a trace – quite literally – for security teams.

Law enforcement officials will deliver an Emotet update, “EmotetLoader.dll” file, which will remove the malware from all infected devices. The run key in the Windows registry of infected devices will be removed to ensure that Emotet modules are no longer started automatically and all servers running Emotet processes are terminated.

However, it is important to note that the switch-off does not remove other malware installed on infected devices via Emotet, nor malware from other sources.

Is this definitely the end of Emotet?

Unfortunately, botnets often return in some form and new variants of very familiar botnets sometimes resurface under a new threat actor’s control. While the takedown of the Emotet botnet by law enforcement agencies is a significant disruption to cybercriminals and should make it difficult for the current Emotet variant to continue, Emotet’s return cannot be ruled out entirely.

Some of the operators behind Emotet are still out there and it is highly likely that they are in possession of copies of the compromised data seized by authorities, as well as other data sets that have not yet been recovered. It is possible that senior members of the Emotet botnet who were not arrested will reassemble.

Historically, Emotet’s operators used long breaks in activity to improve their malware. This means there is a realistic possibility that Emotet’s operators will use this opportunity to make the loader malware even more resilient, for example, by using polymorphic techniques to counter future coordinated action. They could also use the Emotet source code to branch off and create smaller, independent botnets.

Are other cyber gangs taking the place of Emotet?

Since the arrest of the Emotet gang in January, other threat actors (TAs) have been filling the gap in the cybercriminal market. We have seen an increase in activity from TA505, distributing malware families such as IcedID and QakBot.

We have observed multiple clients being targeted by TA505 phishing campaigns and by IcedID activity abusing contact forms published on websites to deliver malicious links to enterprises using emails with fake legal threats.

Several organisations, including the State of Washington, were compromised as a result of the Accellion data breach. These organisations were allegedly infected with the Clop ransomware, highly likely to have been operated by the FIN11 cybercrime group, a spin-off from TA505, and client data was leaked on the “CL0P^_- LEAKS” Tor data leak website.

In the current threat landscape, actors generally move quickly to deploy ransomware once an organisation is infected. While the way into a network may vary, the rest of the kill chain seems to be very similar to what we had previously observed with Emotet.

How do organisations protect themselves against these Emotet-style attacks?

Despite Emotet itself now being inoperable, other malware strains like TrickBot and QakBot remain active and often lead to Ryuk and Egregor ransomware infections. Therefore, it is essential that organisations have adequate controls in place to limit the risk of an infection taking place, and are also ready to detect and respond accordingly.

Ways that organisations can defend themselves include:

- Investing in next-generation antivirus and Endpoint Protection and Response (EDR) tools to help uncover malicious activity in its infancy by monitoring endpoints such as servers and workstations for evidence of suspicious behaviour.

- Disabling macros in attachments by configuring group policy security settings.

- Carrying out regular assessments such as penetration testing, either by an in-house security team or by commissioning an external offensive security team who will help to identify security weaknesses and vulnerabilities.

- Ensuring a stringent patching cycle is adhered to, as these malware strains often still rely on readily patchable exploits to spread autonomously.

- Using a sandbox that can integrate with a next-generation firewall to detect and analyse known or unknown attacks.

- Enforcing multi-factor authentication (MFA) across systems and applications.

- Adhering to the principle of least privilege, so that businesses can significantly reduce the potential damage an attacker can inflict.

- Taking simple steps to securing all managed and unmanaged devices connecting to the network, such as securing Wi-Fi routers and encrypting web traffic.